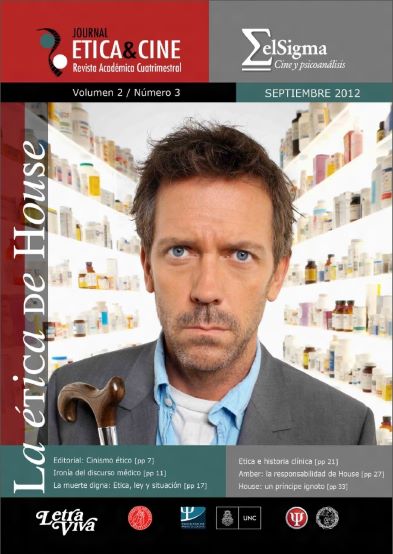

La presencia familiar durante la resucitación médica (RCP) tal como aparece en las series televisivas de gran audiencia: House, Grey´s Anatomy, Medic

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.31056/2250.5415.v2.n3.3001Palabras clave:

Presencia familiar durante la resucitación, PFDR, RCP, TelevisiónResumen

Introducción: Aunque no haya ninguna evidencia científica que refute el beneficio que significa la presencia de la familia durante RCP, los prestadores de la salud persisten en oponerse a ella. Aunque los motivos para esta oposición no han sido dados a conocer, las series televisivas de temas médicos pueden jugar un rol en perpetuarla. Por lo tanto, analizando los modos en que aparece representada la presencia familiar durante las RCP en estos programas, podemos entender mejor los factores que influyen en las actitudes de los profesionales de la salud en este tema, y tal vez utilizar la televisión para modificarlos, de acuerdo con la evidencia científica y las directivas vigentes. Objetivo y metodología del estudio: examinar la manera en que se muestra la presencia familiar durante una resucitación en las nuevas series de dramas médicos en los horarios de gran audiencia, y comparar estas representaciones con una serie televisiva anterior, que también fue exhibida en horario central. Para ello se procedió al visionado y análisis del siguiente material: (a) todos los episodios de la primera temporada de House M.D., (b) Todos los episodios de la primera temporada de Grey’s Anatomy, (c) 16 episodios deMedic. Resultados: En Grey’s Anatomy, la familia está presente en solo una de 12 RCPs. En House M.D., la familia está presente en seis de 14 RCPs. En Medic, la familia estaba presente en el único caso de RCP representado. Conclusión: en la actualidad, las series médicas de mayor audiencia reflejan y probablemente ejercen influencia sobre las actitudes hacia la PFDR (presencia familiar durante resucitación) tanto de la comunidad médica como la del lego. Sin embargo, estas actitudes no se correlacionan con la literatura existente y los lineamentos norteamericanos y europeos. Por lo tanto, los guionistas, legos y profesionales de la salud deberían corregir cualquier opinión no fundamentada que se oponga al a la PFDR y señalar solo aquellos que se basan en evidencia científica.

Referencias

A. Badir, D. S. (2010). Family Presence during CPR: A study of the experiences and opinions of Turkish critical care nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 83-92.

American Heart association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (2000). Ethical aspects of CPR and ECC. Circulation, 102, 12-21.

Ariès, P. (1981). The Hour of Our Death. 1 ed.; Oxford University Press.

A.S. Grice, P. P., C.D.S. Deakin (2003). Study examining attituted of staff, patients and relatives to witnessed resuscitaion in adult intensive care units. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 820, (4), 820-824.

Baer, N. A. (1996). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television: Exaggerations and Accusations (editorial). Vol. 334.

Boehm, J. (2008). Family Presence During Resuscitation. In Codecommunications, Vol. 3.

Bruce M. McClenathan, K. G. T., Catherine F.T. Uyehara (2002). Family Member Presence During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A survey of US and international Critical Care Professionals. Chest, 122, 2204-2211.

C. Dana Critchell, P. E. M. (2007). Should Family Members Be Present During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation? A Review of the Literature. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 24, (4), 311-317.

Chew Keng Sheng, C. K. K., Ahmad Rashidi (2010). A multi-center study on the attitudes of Malasian emergency health care staff towards allowing family presence during resuscitation of adult patients. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3, 287-291.

Christine R. Duran, K. S. O., Jenni Jordan Abel et al (2007). Attitudes Toward and Beliefs About Family Presence: A Survey of Healthcare Providers, Patients’ families, and patients. American Journal of Critical Care, 16, 270-279.

Donald W.Black, N. C. A. (2001). Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry. fifth ed.; American Psychiatric publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, London, England,. p. Xi and 15 respectively.

Dylan Harris, H. W. (2009). Resuscitation on television: Realistic or ridiculous? A quantitative observational analysis of the portrayal of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in television medical drama. Resuscitation, 80, 1275-1279.

Eliot M. Wallack, G. J. B. (1996), Correspondence- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation on Television. New England Journal of Medicine, 335, (21).

Emergency Nurses Association Position Statement (1994). Family Presence at the Bedside During Invasive Procedures and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

Gupta, S. (2009), Cheating Death- The doctors and Medical Miracles that Are Saving Lives Against All Odds. Grand Central Life& Style: New York.

Halm, M. H. (2005). Family Presence During Resuscitation: A Critical Review of the Literature. American Journal of Critical Care, 14, 494-511.

Howard M. Spiro, M. G. M. C., Lee Palmer Wandel (ed) (1996). Facing Death. Yale University Press: New Haven.

Introduction to the International Guidelines 2000 for CPR and ECC: A Consensus of Science. circulation 2000, 102, 1-11.

J Van Den Bulck, K. D. (2004). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on Flemish

television: Challenges to the television effects Hypothesis. Emergency Medicine Journal, 21, 565-567.

Laurie J. Morrison, G. K., Douglas S. Diekema et al. (2010). Ethics: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 122, 665-675.

Manzar Zakaria, M. S. (2008). Presence of Family Members during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation after necessary amendments. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 58, 632-635.

Mary Anne Belanger, S. R. (1997). A rural Community hospital’s experience with family-witnessed resuscitation. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 23, 238-239.

Mason, D. (2003). Family Presence: Evidence Versus Tradition. American Journal of Critical Care, 12, (3), 190-193

Nibert, A. T. (2005). Teaching Clinical Ethics Using a Case Study: Family Presence During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. CriticalCareNurse, 25, 38-44.

Nuland, S. (1993). How We Die. second ed.; Vintage Books, A division of Random House, Inc: New York.

O’Connor, M. M. (1998), The Role of the Television Drama ER in Medical Student Life: Entertainment or Socialization. JAMA, 280, (9).

Oren Wacht (2008). The Attitudes of the emergency department staff toward family presence during resuscitation. Ben- Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva.

Oren Wacht, K. D., Yoram Snir, Nadav Davisovitch (2010). Attitudes of Emergency Department Staff toward Family Presence during Resuscitation. IMAJ, 12.

Paul Fulbrook, J. L., John Albarran, Wouter de Graaf, Fiona Lynch, Denis Decivtor, Tone Norekval (2007). The Presence of Family Members During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: European federation of Critical Care Nursing Association, European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intesive Care and European Society of Cardiology Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions Joint Statement. Connect: The World of Critical Care Nursing, 5, (4), 86-88.

P N Gordon, S. W., P G Lawler (1998). As seen on TV: Observational study of Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in British television medical drama. BMJ, 317, 780-783.

Richard O. Cummins, M. F. H. (2000) The Most Important Changes in the International ECC and CPR Guidelines 2000. Circulation, 102, 371-376.

Ronald J. Market, M. G. S. (1996). Correspondence- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation on Television. New England Journal of Medicine, 335, (21).

Ross, E. K. (2003). On Death and Dying. first ed.; Scribner: New York.

Should Relatives Witness Resuscitation? A report from a Project Team of the Resuscitation Council (UK) Resuscitation Council, UK: London, 1996.

Susan J. Diem, J. D. L., James A. Tulsky (1996). Cardiopulmonary Resuscitaion on Television: Miracles and Misinformation. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1578-1582.

Susan L. MacLean, C. E. G., Cheri White et al (2003). Family Presence During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Invasive Procedures: Practices of Critical Care and Emergency Nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 12, 246-257.

S.M Robinson, S. M.-R., G.L. Campbell Hewson, C.V. Egleston, A.T. Prevost (1998). Psychological effect of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. Lancet, 352, 614-617.

Theivendran, J. (2007), House MD: An analysis of Chronic Pain Managed with Opiate Therapy in Entertainment Television. In Imperial College Medical School: London.

Timmermans, S. (1998). Resuscitation technology on the emergency department: towards a dignified death. Sociology of Health & illness, 20, (2), 144-167.

Timmermans, S. (1999). Sudden Death and the Myth of CPR. 1 ed.; Temple University Press: Philadelphia.

Tsai, E. (2002). Should Family Members Be Present During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation? New England Journal of Medicine, 346, (13), 1019-1021

Turow, J. (1996). Television entertainment and the US health-care debate. Lancet, 347, 1240-1243.

Turow, J. (2010). Playing Doctor: Television, Storytelling, & Medical Power. 2 ed.; The University of Michigan Press: Michigan.

Descargas

Publicado

Número

Sección

Licencia

Los autores que publiquen en Ética y Cine Journal aceptan las siguientes condiciones:

Los autores/as conservan los derechos de autor © y permiten la publicación a Ética y Cine Journal, bajo licencia CC BY-SA / Reconocimiento - Reconocimiento-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional. La adopción de esta licencia permite copiar, redistribuir, comunicar públicamente la obra, reconociendo los créditos de la misma, y construir sobre el material publicado, debiendo otorgar el crédito apropiado a través de un enlace a la licencia e indicando si se realizaron cambios.

Este obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional.