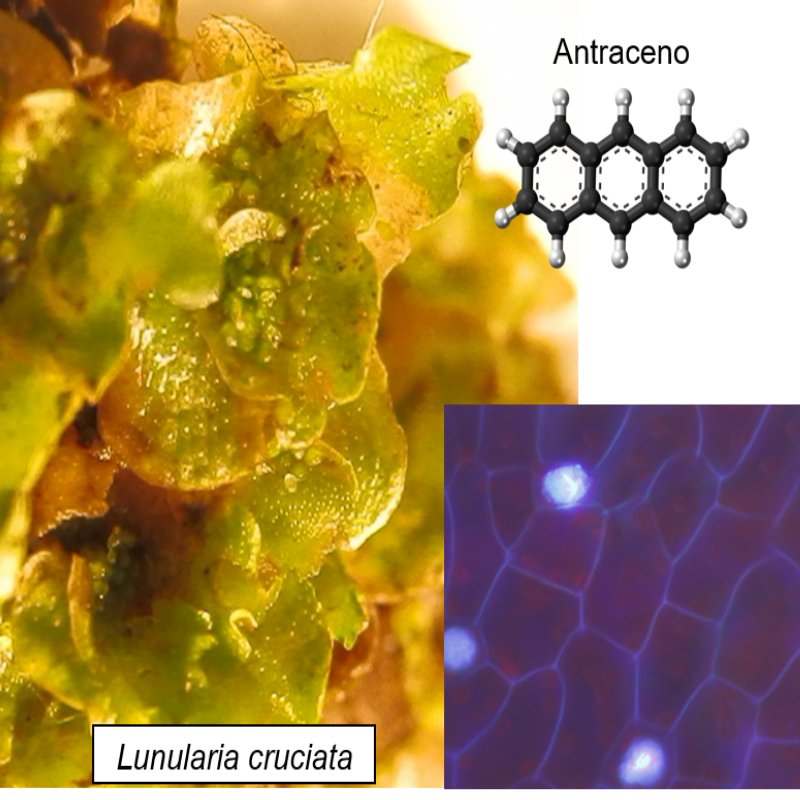

Respuesta fisiológica de Lunularia cruciata (phylum Marchantiophyta) a la presencia del hidrocarburo aromático policíclico antraceno.

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.31055/1851.2372.v56.n4.34219Palavras-chave:

Antraceno, Bioacumulación, Bioindicadora, Lunularia cruciata, ToxicidadResumo

Introducción y objetivos: Los hidrocarburos aromáticos policíclicos (HAPs) son contaminantes ubicuos, persistentes, tóxicos y bioacumulables, generados de la combustión incompleta de la materia orgánica. En plantas vasculares los HAPs causan disminución de la biomasa, alteran el fenotipo e inhiben la fotosíntesis. Actualmente hay poca información acerca de su efecto en las briofitas (sensu lato). Dentro de este grupo, la especie Lunularia cruciata (phylum Marchantiophyta) puede colonizar ambientes con impacto antrópico y es utilizada como bioindicadora de metales pesados. El objetivo de este trabajo fue estudiar los cambios morfológicos y fisiológicos de L. cruciata expuesta al antraceno, para determinar su posible rol como organismo indicador del contaminante.

M&M: Se expuso a esta especie a diferentes concentraciones de antraceno y se evaluó el porcentaje de germinación de las gemas. Además, se determinó en el talo la morfología, crecimiento, bioacumulación y contenido de clorofila.

Resultados & Conclusiones: Se encontró que el antraceno no afectó la germinación de gemas, sin embargo, provocó una morfología “arrosetada” y una disminución del crecimiento en el talo. Por otra parte, se observó que esta especie es capaz de acumular antraceno en la pared celular. El contaminante no afectó el contenido total de clorofila, aunque la relación de clorofilas a y b varió, con una disminución de la clorofila a y un aumento de la clorofila b. Esto podría causar una disminución del rendimiento fotosintético, provocando la reducción del crecimiento de las plantas. Los resultados demuestran que esta especie es tolerante al antraceno y podría ser bioindicadora de HAPs.

Referências

ABDEL-SHAFY, H. I. & M. S. MANSOUR. 2016. A review on Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. of Petroleum. 25: 107-123.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2015.03.011

AKSMANN, A. & Z. TUKAJ. 2004. The effect of anthracene and phenanthrene on the growth, photosynthesis, and SOD activity of the green alga Scenedesmus armatus depends on the PAR irradiance and CO2 level. Arch. of environ. contam. and toxicol. 47: 177-184.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-004-2297-9

ALAM, A. & V. SHARMA. 2012. Seasonal variation in accumulation of heavy metals in Lunularia cruciata (Linn.) Dum. at Nilgiri hills, Western Ghats. Int. J. of Biol. Sci. and Eng. 3: 91-99.

ARANDA, E., J. M. SCERVINO, P. GODOY, R. REINA, J. A. OCAMPO, R. M. WITTICH & I. GARCÍA-ROMERA. 2013. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus custos in the dissipation of PAHs under root-organ culture conditions. Environ. pollut. 181: 182-189.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.06.034

BATES, J.W. 1992. Mineral nutrient acquisition and retention by bryophytes. J. of Bryol. 17: 223-240.

https://doi.org/10.1179/jbr.1992.17.2.223

BÉCARD, G. & J.A. FORTIN. 1988. Early events of vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhiza formation on Ri T‐DNA transformed roots. New Phytol. 108: 211-218.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb03698.x

CARGINALE, V., S. SORBO, C. CAPASSO, F. TRINCHELLA, G. CAFIERO & A. BASILE. 2004. Accumulation, localization, and toxic effects of cadmium in the liverwort Lunularia cruciata. Protoplasma. 223: 53-61.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-003-0028-0

CHANDRA, S., D. CHANDRA, A. BARH, R.K. PANDEY & I.P. SHARMA. 2017. Bryophytes: Hoard of remedies, an ethno-medicinal review. J. of tradit. and complement. med. 7: 94-98.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2016.01.007

GAO, Y., Y. ZHANG, J. LIU & H. KONG. 2013. Metabolism and subcellular distribution of anthracene in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.). Plant and soil. 365: 171-182.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1386-1

GARCÍA-SÁNCHEZ, M., Z. KOŠNÁŘ, F. MERCL, E. ARANDA & P. TLUSTOŠ. 2018. A comparative study to evaluate natural attenuation, mycoaugmentation, phytoremediation, and microbial-assisted phytoremediation strategies for the bioremediation of an aged PAH-polluted soil. Ecotoxicol. and environ. saf. 147: 165-174.

GARREC, J. P. & C. VAN HALUWYN. 2002. Biosurveillance végétale de la qualité de l’ air. In: Tec & Doc (eds.), pp. 117. Paris.

GIORDANO, S., R. CASTALDO COBIANCHI, A. BASILE & V. SPAGNUOLO. 1989. The structure and role of hyaline parenchyma in the liverwort Lunularia cruciata (L.) Dum. G. Botanico italiano. 123: 169-176.

https://doi.org/10.1080/11263508909430255

HARMS, H.H. 1996. Bioaccumulation and metabolic fate of sewage sludge derived organic xenobiotics in plants. Sci. of the Total Environ. 185: 83-92.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(96)05044-9

HÄSSEL DE MENÉNDEZ, G. G. 1959. Estudio de las Anthocerotales y Marchantiales de la Argentina (Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales).

HUANG, X.D., B.J. MCCONKEY, T.S. BABU & B.M. GREENBERG. 1997. Mechanisms of photoinduced toxicity of photomodified anthracene to plants: inhibition of photosynthesis in the aquatic higher plant Lemna gibba (duckweed). Environ. Toxicol. and Chem. 16: 1707-1715.

https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620160819

JAJOO, A., N.R. MEKALA, R.S. TOMAR, M. GRIECO, M. TIKKANEN & E.M. ARO. 2014. Inhibitory effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) on photosynthetic performance are not related to their aromaticity. J. of Photochem. and Photobiol. Biol. 137: 151-155.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.03.011

JAJOO, A. 2017. Effects of environmental pollutants Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) on photosynthetic processes. Photosynthesis: Structures, Mechanisms, and Applications. Springer, Cham., pp. 249-259.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48873-8_11

KEYTE, I., E. WILD, J. DENT & K.C. JONES. 2009. Investigating the foliar uptake and within-leaf migration of phenanthrene by moss (Hypnum cupressiforme) using two-photon excitation microscopy with autofluorescence. Environ. Sci. & technol. 43: 5755-5761.

https://doi.org/10.1021/es900305c

KUMMEROVÁ, M., M. BARTÁK, J. DUBOVÁ, J. TRÍSKA, E. ZUBROVÁ & S. ZEZULKA. 2006. Inhibitory effect of fluoranthene on photosynthetic processes in lichens detected by chlorophyll fluorescence. Ecotoxicol. 15: 121-131.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-005-0037-1

LIU, H., D. WEISMAN, Y.B. YE, B. CUI, Y.H. HUAMG, A. COLON-CARMONA & Z.H. WANG. 2009. An oxidative stress response to Polycyclyc Aromatic Hydrocarbon exposure is rapid and clomplex in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 176: 375-382.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.12.002

MALLAKIN, A., T. S. BABU, D. G. DIXON & B. M. GREENBERG. 2002. Sites of toxicity of specific photooxidation products of anthracene to higher plants: Inhibition of photosynthetic activity and electron transport in Lemna gibba L. G‐3 (Duckweed). Environ. Toxicol. An int. J. 17: 462-471.

https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.10080

MARWOOD, C.A., K.R. SOLOMON & B. W. GREENBERG. 2001. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a bioindicator of effects on growth in aquatic macrophytes from mixtures of PAHs. Environ. Toxicol. and Chem. An int. J. 20: 890-898.

https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620200425

NADAL, M., M. SCHUHMACHER & J. L. DOMINGO. 2004. Levels of PAHs in soil and vegetation samples from Tarragona County, Spain. Environ. Pollut. 132: 1-11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2004.04.003

NYDAHL, A.C., C.K. KING, J. WASLEY, D. F. JOLLEY & S. A. ROBINSON. 2015. Toxicity of fuel-contaminated soil to Antartic moss and terrestrial algae. Environ. Toxicol. and Chem. 34: 2004-2012.

https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3021

OGUNTIMEHIN, I., F. EISSA & H. SAKUGAWA. 2010. Negative effects of fluoranthene on the ecophysiology of tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill): Fluoranthene mists negatively affected tomato plants. Chemosphere. 78: 877-884.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.11.030

SILVANI, V.A., C. P. ROTHEN, M. A. RODRÍGUEZ, A. GODEAS & S. FRACCHIA. 2012. The thalloid liverwort Plagiochasma rupestre supports arbuscular mycorrhiza-like symbiosis in vitro. World J. of Microbiol. and Biotechnol. 28: 3393-3397.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-012-1146-7

SIMS, D.A. & J.A. GAMON. 2002 Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. of environ. 81: 337-354.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00010-X

SPAGNUOLO, V., F. FIGLIOLI, F. DE NICOLA, F. CAPOZZI & S. GIORDANO. 2016. Tracking the route of phenanthrene uptake in mosses: an experimental trial. Sci. of The Total Environ. 575: 1066-1073.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.174

SPINEDI, N., ROJAS, N., STORB, R., CABRERA, J., ARANDA, E., SALIERNO, M., ... & SCERVINO, J. M. 2019. Exploring the response of Marchantia polymorpha: Growth, morphology and chlorophyll content in the presence of anthracene. Plant Physiol. and Biochem. 135: 570-574.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.11.001

TAIZ, L., & E. ZEIGER. 2006. Plant physiology. 4th. Sinauer Associate, Sunderland, Mass., EUA.

TAO, S., Y.H. CUI, F. XU, B. G. LI, J. CAO, W. LIU, G. SCHMITT, X. J. WANG, W. SHEN, B. P. QING & R. SUN. 2004. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in agricultural soil and vegetables from Tianjin. Sci. of the Total Environ. 320: 11-24.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00453-4

VALIÓ, I.F.M. & W. W. SCHWABE. 1969. Growth and dormancy in Lunularia cruciata (L.) Dum.: IV. Light and temperature control of rhizoid formation in gemmae. J. of exp. Bot. 20: 615-628.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/20.3.615

VIVES, I., J.O. GRIMALT & R. GUITART. 2001. Los Hidrocarburos Aromáticos Policíclicos y la salud humana. Apunt. Cienc. Tecnol. 3: 45-51.

WIECZOREK, J.K. & Z. J. WIECZOREK. 2007. Phytotoxicity and accumulation of anthracene applied to the foliage and sandy substrate in lettuce and radish plants. Ecotoxicol. and environ. Saf. 66: 369-377.

Downloads

Publicado

Edição

Seção

Licença

Copyright (c) 2021 R. Storb, N. Spinedi, E. Aranda, S. Fracchia, J. M Scervino

Este trabalho está licenciado sob uma licença Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Proporciona ACESSO ABERTO imediato e livre ao seu conteúdo sob o princípio de tornar a pesquisa livremente disponível ao público, o que promove uma maior troca de conhecimento global, permitindo que os autores mantenham seus direitos autorais sem restrições.

Material publicado em Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. é distribuído sob uma licença Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.