El diámetro del tronco (DAP) y la especie forófita: factores claves que marcan la composición de helechos película (Hymenophyllum, Hymenophyllaceae) en un fragmento de bosque templado de Chile.

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.31055/1851.2372.v59.n4.44499Palavras-chave:

composición florística, Análisis multivariado, bosque nativo, HymenophyllaceaeResumo

Introducción y objetivo: los helechos película (Hymenophyllum) se destacan por su dependencia de micrositios húmedos para su supervivencia, aunque los factores determinantes de su ensamblaje en el hábitat permanecen parcialmente indefinidos. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar cómo cinco variables del hábitat —la orientación del tronco (N-S-E-O), la especie forófita, la presencia de trepadoras, el diámetro a la altura del pecho (DAP), y la cobertura del dosel— afectan la composición de comunidades de helechos película en un fragmento de bosque templado.

M&M: se muestrearon 120 árboles a lo largo de un transecto trazado por el centro del bosque, donde se examinó la presencia-ausencia de helechos hasta una altura de 2.3 m sobre el tronco. El análisis de datos se realizó mediante PERMANOVA con 10.000 permutaciones, seguido de comparaciones múltiples para discernir diferencias en la composición de helechos entre las especies forófitas.

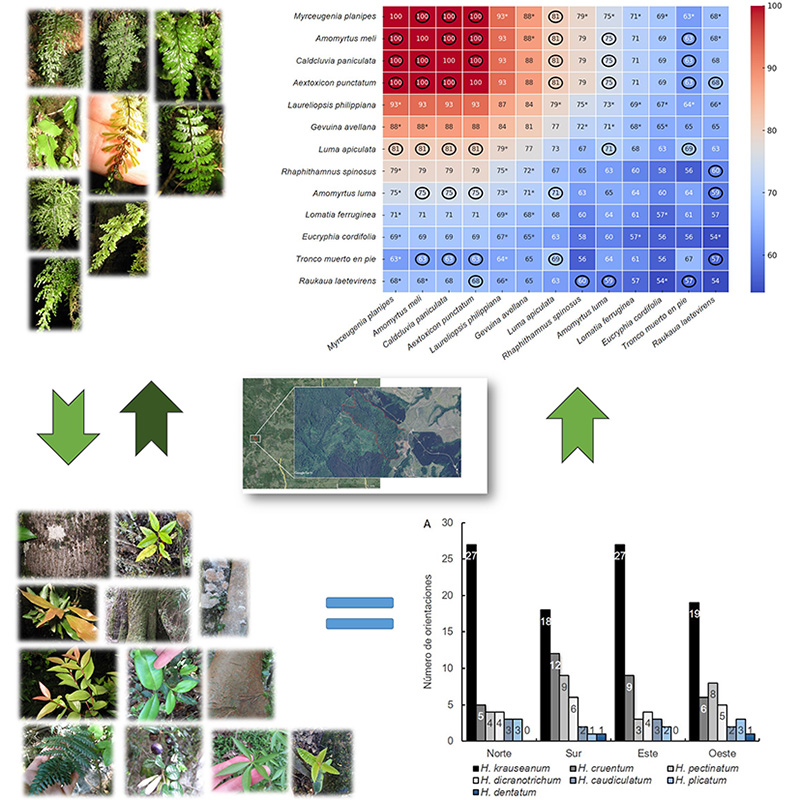

Resultados: se detectó una influencia significativa tanto del DAP de los árboles (Pseudo-F = 21,617; p < 0,001) como de la identidad de las especies forófitas (Pseudo-F = 4,123; P < 0,001). A través de las comparaciones múltiples, se revelaron variaciones significativas (Pseudo-t, p < 0.05) en los ensambles de helechos asociados a grupos de especies forófitas.

Conclusiones: Los resultados indican que ciertas características físicas y bióticas del forófito son cruciales para la estructuración de las comunidades de helechos película, otros factores ambientales considerados inicialmente podrían no ser tan importantes o su efecto podría estar enmascarado por la homogeneidad de las condiciones de muestreo, tamaño muestreal insuficiente o efecto de perturbaciones antrópicas.

Referências

ANDERSON, M. J., R. GORLEY & K. CLARKE. 2008. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: guide to software and statistical methods. PRIMER-e, Aucklandd.

ANDERSON, M. J. & D. C. WALSH. 2013. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: What null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 83: 557-574. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-2010.1

ARAGÓN, G., L. ABUJA, R. BELINCHÓN & I. MARTÍNEZ. 2015. Edge type determines the intensity of forest edge effect on epiphytic communities. Eur. J. Forest Res. 134: 443-451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-015-0868-7

ARROYO-RODRÍGUEZ, V. & T. TOLEDO-ACEVEDO. 2009. Impact of landscape spatial pattern on liana communities in tropical rainforests at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Appl. Veg. Sci. 12: 340-349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-109X.2009.01030.x

BAUTISTA, L., A. DAMON, S. OCHOA-GAONA & R. TAPIA. 2014. Impact of silvicultural methods on vascular epiphytes (ferns, bromeliads, and orchids) in a temperate forest in Oaxaca, Mexico. Forest Ecol. Managem. 329: 10-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.05.053

BERNASCHINI, M., G. VALLADARES & A. SALVO. 2020. Edge effects on insect-plant food webs: assessing the influence of geographical orientation and microclimatic conditions. Ecol. Entomol. 45: 806-820. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12854

BIERREGAARD, R. O., T. LOVEJOY, V. KAPOS, A. A. DOS SANTOS & R. W. HUTCHINGS. 1992. The biological dynamics of tropical rainforest fragments: A prospective comparison of fragments and continuous forest. BioScience 42: 859-866. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312085

DE MEDEIROS, P. M., G. M. C. DOS SANTOS, D. M. BARBOSA, L. C. A. GOMES … & R. R. V. DA SILVA. 2021. Local knowledge as a tool for prospecting wild food plants: experiences in northeastern Brazil. Scientific Reports 11: 594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79835-5

DIECKMAN, M., A. KÜHNE & M. ISERMANN. 2007. Random vs non-random sampling: effects on patterns of species abundance, species richness and vegetation-environment relationships. Folia Geobot. 42: 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02893884

DIEM, J. & J. LICHTENSTEIN. 1959. Las Himenofiláceas del área argentino-chilena del sur. Darwiniana 11: 611-760.

DUBUISSON, J.-Y., H. SCHNEIDER & S. HENNEQUIN. 2009. Epiphytism in ferns: diversity and history. Comp. Rend. Biol. 332: 120-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2008.08.018

FLORES-BAVESTRELLO, A., M. KRÓL, A. IVANOV, N. HÜNER, J. García-Plazaola, L. Corcuera & L. BRAVO. 2016. Two Hymenophyllaceae species from contrasting natural environments exhibit a homoiochlorophyllous strategy in response to desiccation stress. J. Pl. Physiol. 191: 82-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.11.011

GARCÉS, M., C. STEPHAN, C. ALVEAR, C. RABERT & L. BRAVO. 2014. Desiccation tolerance of Hymenophyllacea filmy ferns is mediated by constitutive and non-inducible cellular mechanisms. Comp. Rend. Biol. 337: 235-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2014.02.002

GIANOLI, E., A. SALDAÑA, M. JIMÉNEZ-CASTILLO & F. VALLADARES. 2010. Distribution and abundance of vines along the light gradient in a southern temperate rain forest. J. Veg. Sci. 21: 66-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01125.x

HOBBS, R. J. & L. F. HUENNEKE. 1992. Disturbance, Diversity, and Invasion: Implications for Conservation. Conservation Biol. 6: 324-337.

HOEBER, V. & G. ZOTZ. 2021. Not so stressful after all: Epiphytic individuals of accidental epiphytes experience more favourable abiotic conditions than terrestrial conspecifics. Forest Ecol. Managem. 479: 118529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118529

KELLY, B., R. GROSS, K. BITTINGER, S. SHERRILL-MIX … & H. LI. 2015. Power and sample-size estimation for microbiome studies using pairwise distances and PERMANOVA. Bioinformatics 31: 2461-2468. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv183

KENKEL, N. C., P. JUHÁSZ-NAGY & J. PODANI. 1989. On sampling procedures in population and community ecology. Vegetatio 83: 195-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00031692

LARSEN, C., M. PONCE & A. SCATAGLINI. 2013. Revisión de las especies de Hymenophyllum (Hymenophyllaceae) del sur de Argentina y Chile. Gayana, Bot. 70: 274-329.

https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-66432013000200009

LAURANCE, W., W. LAURANCE, J. CAMARGO, R. LUIZÃO … & T. LOVEJOY. 2011. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: A 32-year investigation. Biol. Conservation. 144: 56-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.09.021

LUEBERT, F. & P. PLISCOFF. 2006. Sinopsis bioclimática y vegetacional de Chile. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago.

MARTICORENA, C. & R. RODRÍGUEZ. 1995. Flora de Chile. Vol I Pteridophyta-Gymnospermae. Universidad de Concepción, Concepción.

MEHLTRETER, K. 2010. Fern conservation. En; K. MEHLTRETER et al. (eds.), Fern Ecology, pp. 323-359. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

MICHEL, A. & S. WINTER. 2009. Tree microhabitat structures as indicators of biodiversity in Douglas-fir forests of different stand ages and management histories in the Pacific Northwest, U.S.A. Forest Ecol. Managem. 257: 1453-1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.11.027

MUÑOZ, A., P. CHACON, F. PEREZ, E. BARNERT & J. ARMESTO. 2003. Diversity and host tree preferences of vascular epiphytes and vines in a temperate rainforest in southern Chile. Austral. J. Bot. 51: 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT02070

NICOLAI, V. 1986. The bark of trees: thermal properties, microclimate and fauna. Oecologia 69: 148-160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00399052

ORTEGA-SOLÍS, G., I. DÍAZ, D. MELLADO-MANSILLA, F. TELLO … & C. TEJO. 2017. Ecosystem engineering by Fascicularia bicolor in the canopy of the South-American temperate rainforest. Forest Ecol. Managem. 400: 417-428.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.06.020

PARRA, M. J., I. DÍAZ, D. MELLADO-MANSILLA, F. TELLO … & C. TEJO. 2009. Vertical distribution of Hymenophyllaceae species among host tree microhabitats in a temperate rainforest in southern Chile. J. Veg. Sci. 20: 588-595. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40295772

PINCHEIRA-ULBRICH, J., C. HERNÁNDEZ & A. SALDAÑA. 2018. Consequences of swamp forest fragmentation on assemblages of vascular epiphytes and climbing plants: Evaluation of the metacommunity structure. Ecology and Evolution 8: 11785-11798.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4635

PINCHEIRA-ULBRICH, J., C. E. HERNÁNDEZ, A. SALDAÑA, F. PEÑA-CORTÉS & F. AGUILERA-BENAVENTE. 2016. Assessing the completeness of inventories of vascular epiphytes and climbing plants in Chilean swamp forest remnants. New Zealand J. Bot. 54: 458-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2016.1218899

PINCHEIRA-ULBRICH, J., J. R. RAU & C. SMITH-RAMIREZ. 2012. Diversidad de plantas trepadoras y epífitas vasculares en un paisaje agroforestal del sur de Chile: una comparación entre fragmentos de bosque nativo. Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 47: 411-426.

PINCHEIRA-ULBRICH, J., J. R. RAU, y E. HAUENSTEIN. 2008. Diversidad de árboles y arbustos en fragmentos de bosque nativo en el sur de Chile. Phyton (Buenos Aires). 77: 321-326.

PTERIDOPHYTE PHYLOGENY GROUP I (PPG I). 2016. A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. J. Syst. Evol. 54: 563-603.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12229

REYES, F., S. ZANETTI, A. ESPINOSA & M. ALVEAR. 2010. Biochemical properties in vascular epiphytes substrate from a temperate forest of Chile. Revista de la Ciencia del Suelo y Nutrición Vegetal 10: 126-138. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-27912010000200004

RODRÍGUEZ, R., D. ALARCÓN & J. ESPEJO. 2009. Helechos nativos del centro y sur de Chile: Guía de campo. Editorial Corporación Chilena de la Madera, Concepción.

SALDAÑA, A., M. PARRA, A. FLORES-BAVESTRELLO, L. CORCUERA & L. BRAVO. 2014. Effects of forest successional status on microenvironmental conditions, diversity, and distribution of filmy fern species in a temperate rainforest. Pl. Spec. Biol. 29: 253-262.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1442-1984.12020

SEVER, K. & T. NAGEL. 2019. Patterns of tree microhabitats across a gradient of managed to old-growth conditions. Acta Silvae et Ligni 118: 29-40 https://doi.org/10.20315/asetl.118.3

SHMIDA, A. & S. ELLNER. 1986. Coexistence of plant species with similar niches. Vegetatio 58: 29-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00044894

STEIN, A., K. GERSTNER & H. KREFT. 2014. Environmental heterogeneity as a universal driver of species richness across taxa, biomes and spatial scales. Ecol. Letters. 17: 866-880. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12277

TAYLOR, A., A. SALDAÑA, G. ZOTZ, C. KIRBY … & K. BURNS. 2016. Composition patterns and network structure of epiphyte-host interactions in Chilean and New Zealand temperate forests. New Zealand J. Bot. 54: 204-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2016.1147471

VAN DER HEIJDEN, G. & O. PHILLIPS. 2008. What controls liana success in Neotropical forests. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 17: 372-383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00376.x

WAGNER, K., G. MENDIETA-LEIVA & G. ZOTZ. 2015. Host specificity in vascular epiphytes: a review of methodology, empirical evidence and potential mechanisms. AoB Plants 7: plu092. https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plu092

WAHEED, M., S. HAQ, K. FATIMA, F. ARSHAD … & K. YESSOUFOU. 2022. Ecological distribution patterns and indicator species analysis of climber plants in Changa Manga Forest Plantation. Diversity. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14110988

WANG, X., W. LONG, B. SCHAMP, X. YANG … & M. XIONG. 2016. Vascular epiphyte diversity differs with host crown zone and diameter, but not orientation in a tropical cloud forest. PLoS ONE 11: e0158548. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158548

WICKLEIN, H., D. CHRISTOPHER, M. CARTER & B. SMITH. 2012. Edge effects on sapling characteristics and microclimate in a small temperate deciduous forest fragment. Nat. Areas J. 32: 110-116. https://doi.org/10.3375/043.032.0113

WODA, C., A. HUBER & A. DOHRENBUSCH. 2006. Vegetación epífita y captación de neblina en bosques siempreverdes en la Cordillera Pelada, sur de Chile. Bosque (Valdivia). 27: 231-240. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002006000300002

WOODS, C. 2017. Primary ecological succession in vascular epiphytes: The species accumulation model. Biotropica 49: 452-460. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12443

ZOTZ, G. & M. BADER. 2009. Epiphytic plants in a changing world: global change effects on vascular and non-vascular epiphytes. Progr. Bot. 70: 147-170.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68421-3_7

Referencias de Figuras y de Tablas

Tabla 1. Resultados del análisis PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) para la composición de especies de la comunidad de helechos película (Hymenophyllum spp.) y su relación con algunas variables del hábitat forestal. Fuente: fuentes de variación. df: grados de libertad asociados a cada fuente de variación. SS: Suma de cuadrados, que indica la variación total asociada a cada fuente de variación. MS: media cuadrática. P(perm): Valor p obtenido a través del proceso de 10000 permutaciones. Pseudo-F: estadístico análogo al valor F en ANOVA tradicional. Unique perms: Número de permutaciones únicas realizadas para la prueba. Los asteriscos (**) representan combinaciones de niveles de factores para los cuales no hay datos disponibles o las celdas están vacías.

Fig. 1. Área de estudio en la Región de Los Lagos, Chile.

Fig. 2. Resumen de los componentes del hábitat y la presencia de helechos película en 480 orientaciones (micrositios) de troncos forófitos. A: composición de especie de helechos por orientación (Norte-Sur-Este-Oeste). B: Diagrama de caja de la cobertura del dosel (%) por orientación. C: Número de orientaciones por especie forófita (barras negras) y presencia de helechos película (barras grises). D: Distribución diamétrica de los árboles (barras negras) y presencia de helechos película (barras grises). E: Orientaciones ocupadas por helechos película y trepadoras en los troncos.

Fig. 3. Mapa de calor de similitud florística de helechos película entre especies forófitas y comparaciones múltiples con pseudo-T posteriores al PERMANOVA. Símbolos= *: asteriscos indican diferencias significativas (p < 0,05); ○: óvalos representan combinaciones con tamaño de muestra insuficiente.

Downloads

Arquivos adicionais

Publicado

Edição

Seção

Licença

Copyright (c) 2024 Jimmy Pincheira-Ulbrich

Este trabalho está licenciado sob uma licença Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Proporciona ACESSO ABERTO imediato e livre ao seu conteúdo sob o princípio de tornar a pesquisa livremente disponível ao público, o que promove uma maior troca de conhecimento global, permitindo que os autores mantenham seus direitos autorais sem restrições.

Material publicado em Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. é distribuído sob uma licença Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.